Interview with Featured Poet

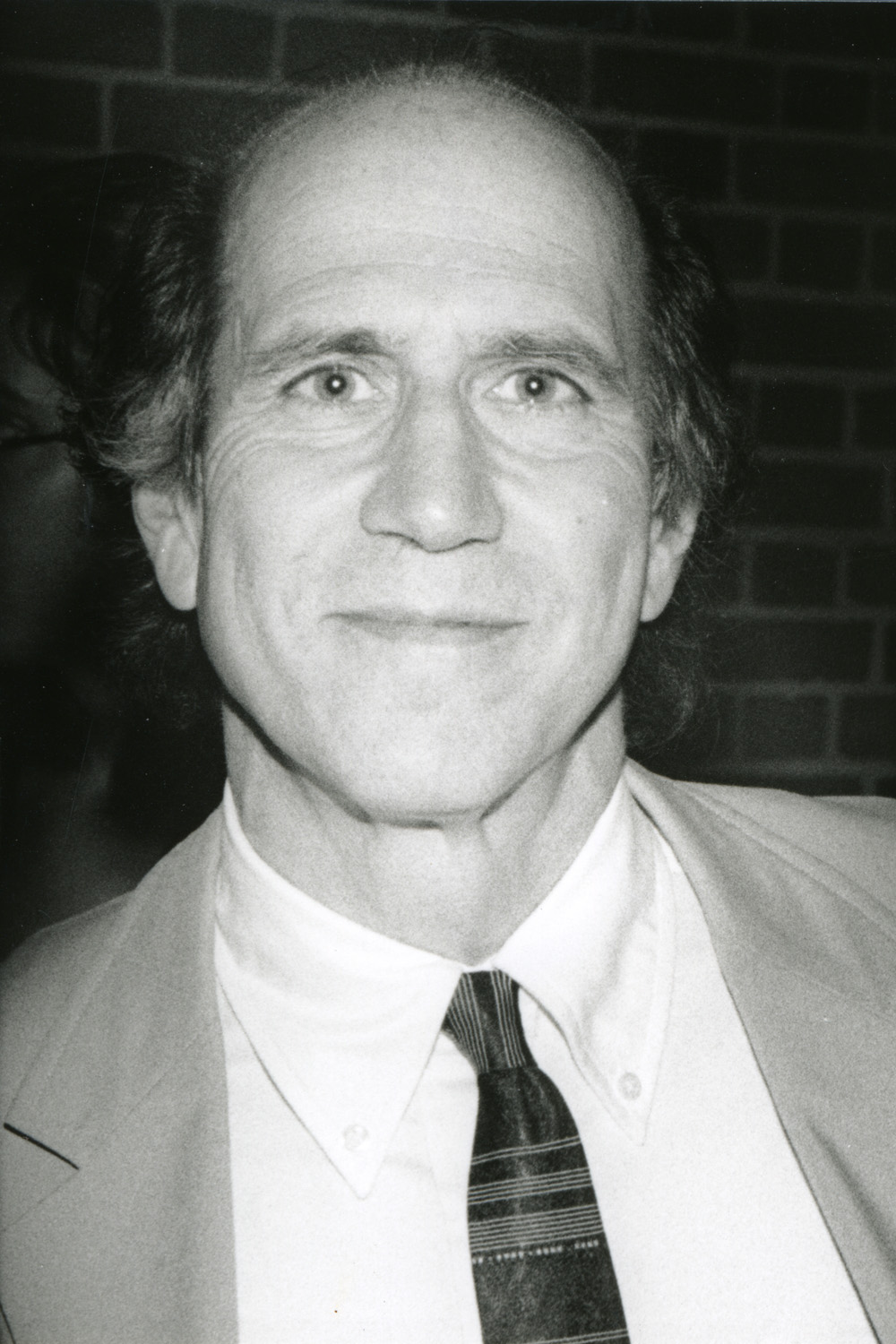

Joseph Bathanti

[TCP] After having read This Metal (St. Andrews College Press, 1996), Anson County (Parkway Publishers, 2005), Land of Amnesia (Press 53, 2009), and Restoring Sacred Art (Star Cloud Press, 2010), I find your poetry preoccupied with understanding the past, the act of remembering, the act of forming identity, and family. Can you speak specifically to the motif of family and how it has developed in your work? [JB] I suppose it’s safe to say that I’m obsessed with both the past and family. The dual and ongoing loss of both, if you will, often drives my work. I find the act of remembering an act of praise, a daily office that’s restorative. Indeed that sense of prayerful commemoration is the reason I titled my most recent book of poems Restoring Sacred Art. In it, and in my other books, I invoke the dead, but the living as well. A number of the poems in this latest volume are characteristically about my parents and about others, dear to me (notably Philip DeLucia, my great friend and my First Holy Communion partner, whose painting, Exaltation, graces the book’s cover), who are now gone. Restoring Sacred Art contains the first batch of poems about my parents that I published after their deaths. It is decidedly hubris on my part – but not blasphemy – to beatify the dead by resurrecting them in my writing. Dorothy Day believed that prayers for the dead help them while they were living on earth. Perhaps poems serve the same function. There’s that famous passage in The Great Gatsby where Nick Carraway warns Gatsby: “’You can’t repeat the past.’” Gatsby counters emphatically with “Why of course you can!” I tend to agree with Gatsby. One must often summon the dead to channel the past. I should point out, for the sake of parity, that my wife is from Georgia. We’ve been together nearly thirty-five years. Therefore I have a Southern family as well. Their intimacies and fractures – their “mystery and manners,” to invoke the famous Catholic Georgian, Flannery O’Connor, whose work has mightily influenced me – intrigues me as well. Family, not just for me, is the universal bedrock of stories and poems (and, my heavens, look at the family memoirs – often tortured – hurtling at us by the score). What else is there? The Bible is, after all, one long, long outrageous genealogy. [TCP] I also notice that you bring together myth and religious themes in your poetry quite often, lending the poems an air of timelessness and profundity. Can you speak to why you choose to bring these ideas together—particularly the conflation of classic mythology with overtly Christian lore? [JB] I’m seemingly unable to write about anything without Catholicism infiltrating it. I went to a public kindergarten. After that, the next twelve years of my education occurred in Catholic schools. For those twelve years, I wore a necktie and a sports jacket. In grade school, I was taught by nuns, Sisters of Divine Providence and Sisters of Charity. There was little providence and zero charity. I despised the nuns, and apparently the feeling was mutual. I was, if you will, a bad boy, and they beat me regularly, and unmercifully, and were inventively psychologically abusive as well. This will come as no revelation to people my age that attended Catholic schools in the 50s and 60s. Mean nun stories are legion and wonderfully diverse and unspeakably funny – in an excruciating kind of way. My sincere apologies to those nuns who have never tortured little school children. I know they are out there – I even met a few, very very few, in my sojourn through grade school – but I’ll have to stand by my experience. I am, however, grateful to them. They taught me to read and to form words on the page; and then they gave me, through their outlandish behaviors, a lifetime of stories and poems to write. In high school, I was taught by Christian Brothers, wonderful men – tough, fair and square and never gratuitous in their discipline. In fact, I just spent a week as Writer-in-Residence at my high school Alma Mater, Pittsburgh Central Catholic. So I haven’t separated myself from my Catholic roots; though, lest I give the wrong impression, I should point out that I am no longer what the church terms a ‘practicing” Catholic – I do not practice the religion in the sanctioned public manner dictated by dogma – though I consider myself a congenital Catholic, perhaps a DNA Catholic. Technically, I’m excommunicated (but only technically): I married a Southern Baptist in Indian Creek Baptist Church in Stone Mountain, Georgia. I want to be very clear on something. I have no quarrel with the Catholic Church, though clearly I take exception to their stances regarding marriage and reproduction. As a writer, I would be absolutely nowhere without Catholicism and the ritual, sacramental life it has instilled in me. As a kid, I was of course traumatized by the notion of hell forwarded in my Catechism, but not so much as my Southern Fundamentalist counterparts I’d meet once I travelled south in 1976. To them, the devil was decidedly a three dimensional temporal creature who might jerk you out of your bedclothes at any moment. My religious indoctrination was exclusively confined to the schoolhouse. Though our home was spangled generously with the usual array of Catholic iconography – crucifixes, rosaries, scapulars, statues, ceramic Madonnas that doubled as dish gardens, wall fonts for holy water and much much more (perhaps more dramatic in Italian households like ours), my parents, thank God, did not prattle about religion. We said Grace before dinner (only) and my Mother often adjured me to “say a few prayers” when I complained about sleeplessness. I figured to escape hell through Purgatory: painful, yes, but not eternal. And of course, there was Confession which could wipe away all traces of sin if you had the gumption to actually tell the priest the truth once you entered the confessional – which I could never muster. The rhythm of my boyhood, through high school, was dictated by Catholicism. In my neighborhood, no matter what direction you turned, the steeple of one Catholic Church or another punctuated the horizon. In truth, I was rather in love, completely enchanted, by the pomp and mystery of Catholicism. I was a choir boy and an altar boy. I went to mass every day except Saturday, grades 1 through 5. Belting out the Tantum Ergo from the choir loft, while the gorgeous blonde organist I was secretly in love with shook the massive ornate, shimmering fortress of a church with her licks, filled me with euphoria. If it was not a movement of the spirit, I’d at least call it religious. And certainly the lore and stories of the saints and martyrs dispensed to us every day in Religion class had an overwhelming influence on me. When I moved to the South in 1976, I not only could hold my own when it came to the Bible, but I could best most of those Protestants. So I was steeped in stories, much of it gruesome, but infinitely alluring to a kid of my pedigree. I adored those stories. The sheer mystery of it all blew my mind, and I was enchanted by the sacraments. How pompous of me to say, but I found in Jesus from the very beginning a kindred spirit. I turned to Him for understanding. I always felt terribly sorry for Jesus. I also want to say that, despite my incessant disparaging of the nuns, I found their histrionics, even their beatings, terrifically funny – even when I was the one crooked over a desk awaiting their fury. It was beneath the flail of their sticks and bludgeons that I discovered irony. After a beating, it was protocol to say to your assailant, “Thank you, Sister,” to which she politely responded, “You’re welcome, Mr. Bathanti.” Thus when it came time for me to turn my hand to writing seriously – not about other planets or dragons and wizards – I found that my central store of material lay in autobiography, and that autobiography for me was synonymous with having grown up steeped in Catholicism (a decidedly Italianate version) and my concomitant Catholic education. Yes, in my poems, Prometheus and Actaeon and Oedipus and Sisyphus (who instantly captured my imagination after reading Camus’s “The Myth of Sisyphus” in high school), tend to make cameos in my poems. But the mythic characters have always been the people I’ve known. I think that all poets, particularly the high Confessionals, with whom I feel in their lighter moments a kinship – like Lowell, for instance – were always hatching out of their own lives, and the people orbiting them, their own private mythos. [TCP] Place plays an extremely crucial role in your work, particularly Anson County. Now that you have moved to western North Carolina, has identifying yourself as an Appalachian poet influenced your work at all? Tell us how place, particularly the Appalachian South, influences your work. Are there distinctions—other than the difference of landscape—that you feel distinguish Appalachian Southern poetry from Southern poetry in general, particularly in your work? [JB] I was once at a reading by Fred Chappell and, after it, someone in the audience asked Fred to talk about being a Southern writer. Fred was quick to point out that he was an Appalachian writer. That was the first time I ever contemplated the distinction. I have always felt extremely honored to have been admitted into the ranks of Southern writers, North Carolina writers to be precise. So I suppose I was wearing that mantle gingerly when we moved to Vilas, a little town just outside Boone, after I took a teaching job at Appalachian State University. Again, more than anything, my practice is to gaze out my window and write about what I see – unless, of course, I am plumbing the vaults of my memory. If imagery is language that appeals to the senses – and it is – then, living here in Appalachia, I’ve been afforded a whole new set of senses with which to write. What a gift. I believe that place, just about more than anything – of late, I’ve been on a real kick with my students about place and its indisputable power to contextualize and authenticate dramatically what one writes – brings expert eyewitness authority to a piece of writing. Place can be every bit as powerful as character. [TCP] We very much enjoyed the prefatory prose statement to your book, Anson County. In this prose introduction, you describe several preternatural occurrences: overheard conversation in other rooms of a very old house; eerie, zig-zagging, lights in the night sky that no aircraft could replicate; the feeling of ghostly presences in certain rooms. As a poet who seeks symbols in the tangible and who willfully interprets the divine in the explainable, can you speak more to your ideas about ontology and the presence of the supernatural or divine and how it dovetails with your work? Do you believe that there are unfathomable presences that serve as muses for certain, few writers? [JB] That sense of “another presence” began when my wife, Joan, and I moved from Charlotte to Anson County in the summer of 1985. Charlotte was the first place I landed when I came south from Pittsburgh in 1976 to work in the North Carolina prison system as a VISTA Volunteer. The transition from Pittsburgh to Charlotte was smooth as silk. I had come to North Carolina looking for the South – though my idea about what the South was had been heavily influenced by what I’d seen in the movies, though I had read my share of Faulkner, Welty and O’Connor. Nevertheless, my notion of the South, back then, was still Gone with the Wind, as vacuous as that may seem. Just as my notion of Africa was the Tarzan movies with Johnny Weissmuller. Charlotte, in 1976, was a small city, but a city nonetheless, and the contrast between it and my home town of Pittsburgh did not strike me as dramatic. In fact, one seemed hard pressed to find native North Carolinians there at the time, and my closest friends were from Philadelphia, Cleveland, Chicago, and New York. Joan was often the lone Southerner in that nest of expatriate Yankees – and she made sure we knew it. She and I lived in Charlotte for 8 years. I taught at Central Piedmont Community College, a wonderful place, my first teaching job. And then, in 1985, I took a job as Writer-in-Residence at Anson Technical College in Wadesboro, North Carolina, about 60 miles east of Charlotte, in the proverbial (and quite literal) middle of nowhere. Anson County is actually the place where Steven Spielberg filmed The Color Purple. And, a few years later, the cult classic Evil Dead II was shot there, in which incidentally I had a role as an extra. Perhaps it’s every city kid’s dream to live in the country. It had certainly always been mine. In Anson, we lived in a two storey shotgun house with no conventional heat system. It was eleven miles from the nearest quart of milk. For someone who had grown up in a row house and could nearly spit on my neighbors across our one way street, living in that wilderness was mind-blowing. I had finally found the South. In fact, the New York Times News Service would assert in 1992 that “with a 97.2 percent concentration of native Southerners … Anson County is as Dixie as you can get.” It was there in Anson that I became a Southern poet, and there as well that I began to invest in and invoke the Muse. Some kind of transformation occurred once I moved there, and I’d like to call it supernatural, though I don’t want to disguise what really may have happened by ascribing it to the inscrutable. But here’s what I know. We lived in a haunted house where we heard voices, though we were never afraid. My wife was pregnant there with our first child, and that pregnancy in some ways abetted whatever was changing in my work. I had started writing almost pathologically poem after poem – they just kept coming – about the place I was suddenly living in: the house, the trees, the wildlife, the crops, the rivers and streams. I was in the spell of that place, totally enchanted, and all of it informed by the utter unlikelihood that another one of us, that Joan and I had somehow engendered – “unfathomable presences” as you put it in your question – was growing moment to moment in my wife’s womb. Talk about ontology. That very place, Anson County, was my muse. That land was ancient and had a mind and a soul of its own. It was actually miraculous. I was a stranger there. Every day, I wrote in a country diner called The Hub, arguably the most popular of what I still regard as Anson County’s truly spectacular array of old-fashioned Southern country-cooking diners and cafes back then. The Hub sat on a flat punished expanse of U.S. 74, not much more than a race track for 18-wheelers, on the outskirts of Wadesboro. Judging from its Spartan exterior, it did not seem an establishment that would gladly suffer poets. Inside its walls were festooned with deer heads, mounted bass and speckled trout. The floors were worn tile, scuffed nearly to plyboard, but immaculate. It’s A sanitation rating was displayed prominently on the back of the cash register, and next to the register were a jar of toothpicks and a March of Dimes canister. I studied the county map, I read and lugged around with me History of Anson County, by Mary Medley, a writer to whom I feel indebted. I found out that when first formed in 1750, Anson County, named for George Anson (Lord Anson to the locals), a British Admiral born in the 17th century, stretched as far west as the Mississippi, and to the east as far as what we now know as the Lumber River in Robeson County, clear north to the Virginia border and south to the South Carolina border. Purportedly the entire state of Tennessee was carved out of the original Anson Charter. Blues legend, Blind Boy Fuller, born Fulton Allen, was born in Anson. A little known, yet cherished fact, is that Anson County produces a grade of the world's finest gravel. I made pilgrimages to Bethlehem Cemetery and the ghost town of Sneedsborough, the last known sighting of Aaron Burr’s daughter, Theodosia, before she stepped into her boat and floated down the Pee Dee River. I scoured roads from Caisson-Oldfield to Burnsville, Peachland to the O.B. Hardison Bridge. I explored abandoned buildings and wandered woods and fields, taking notes, taking photographs, keeping a journal, toting around a tape recorder. I learned to cut and split wood, the difference between white and red oak, how to recognize a hog-nosed snake from a copperhead; tasted deer meat and detonated a shotgun for the first time and sort of learned to ride a horse. Maybe it was sitting day after day in The Hub and hearing those timber trucks thrum from Wilmington to Asheville, or listening to tobacco farmers talk about “big leg” and “blue mold,” how the cooks barged through the aluminum swing doors to replenish the steam table with vats of fried chicken and okra and I’d hear for a split second gospel singing from the kitchen. The waitresses at The Hub kindly replenished my coffee as I filled legal pads with scribbled poems, one after another – enough poems for what looked like a book. The book that would become Anson County. And then our son, Jacob, was born – a baby boy – an event that can surely be explained by science, but not satisfactorily by my lights. The muse is always an unfathomable presence. And, by the way, Joan and I did see a space ship. [TCP] Conversely, in your collection Land of Amnesia, your poetry seems to evolve into a more chiseled, direct style, in which certain poems (such as the beautiful “Epigenesis”) employ scientific diction and the second-person pronoun “you.” Though you use scientific terms such as “gymnosperm” and “igneous” to texture the poem and target the reader directly, this piece remains a mysterious exploration of the other, surreal world, where even the “unimagined” returns. With this poem and others in Amnesia, you remind us of A.R. Ammons or Alison Hawthorne Deming, poets who champion hard science as a device that, paradoxically, leads the reader to abstract, unanswerable questions. Can you speak a bit to the use of science in your poetry? [JB] While I am decidedly interested in science, I’ve never thought of myself as having a bent toward it. Nor have I considered it an influence on my poems, or manifesting itself within them. So I’m truly flattered if some latent penchant for science has leaked into them. However, I am captivated by the mystery of the natural world. I think I always have been, but after moving to from Pittsburgh to North Carolina in 1976, I found myself surrounded in more obvious ways by the natural world. Then, when we moved to Anson County, the natural world became my muse and trope. I did not become Adam; I did not name things. But I learned the names of things, and names (the specificity of designation) have always fascinated me, and I like to name names in my work. The proper names of things are authenticating agents. Thus, instead of knowing that something was merely a flower, I found out, tutored by my Southern wife, that it was Sweet William or Ageratum or Joseph’s Coat, or Lamb’s Ear. How beautiful, I thought. Syllables and music, that wondrous aural quality that defines the best poetry. Everything has a name. I stared from our bedroom window at tobacco plants bathed in moonlight. I regularly saw herds of deer, rattlesnakes, and cottonmouths. I killed copperheads. I heard wildcats scream. I looked into the eyes of a red fox. I found arrowheads and shed antlers. It was magical and it was surreal. I think, at least as it pertains to my work, I’d prefer to substitute for the word science the word numen which means “divine power or spirit; a deity, especially one presiding locally or believed to inhabit a particular object.” I’m obsessed with the mystery of things that always, if you will, deadend into God, or at least the notion of God. Words like gymnosperm and igneous result in my work from my poking around in dictionaries and strange monographs on natural history, and perhaps I do take some cues from A.R. Ammons, a fabulous and fabulist poet who I’ve always admired. I habitually do research, living and archival, into certain subjects I find myself writing about; and, out of that research, one might turn up a word like gymnosperm – which is too extraordinary to not use in a poem and, truly, the use of such scientific terms tends to authenticate a poem. I’m also drawn to words because of their sounds and, when they mean something in addition, well, then you’ve struck it rich. Numen helps you say what can’t be said. The poem is always smarter than the poet – and smarter than science, for that matter. I am not a creationist, God forbid, but I do like to think that God predates television. [TCP] Returning to the idea of place, in your collection, Restoring Sacred Art, you draw on a deep well of memories associated with Pittsburgh, PA. In your estimation, how does this particular place—markedly similar in the surrounding landscape but distinctly different in tone and immediate environment—inform your work differently than those poems written about relatively rural areas? Certainly your childhood plays a large part of the Pittsburgh-centered poems, but do you detect any differences in execution of the writing itself when Pittsburgh informs the work? [JB] Pittsburgh is a city inebriated on its own mythology: steel, the Steelers, its pigheaded refusal to give up or give in, its swagger in the face of relentless weather and sunless days, the fact that it is a reliquary of its former self as the world’s steel center; yet what molted out of the demise of steel is the glory of its artistic temperament, a maelstrom of ethnicity, its three famous rivers. If it were a saint, it would be the martyr Lawrence, roasted on a gridiron, who asked to be turned over because he was done on one side. The city is that tough, and it thrives on spiting itself – like a lot of those crazy fabulous Italians I come from. If you grow up in Pittsburgh, and your bent is toward writing, then as you mature you will find yourself steeped in the city’s inescapable mythology. In my case, my reflex has been to write about that place not just in my poetry, but also in my fiction and nonfiction (though I must insist that I write about the South just as reflexively these days). So there was, growing up, the greater place of Pittsburgh, but I remain convinced that the place that evangelized me more than anywhere was my neighborhood, one of Pittsburgh’s all but vanished Little Italys: East Liberty (also the title of my first novel). And within that place, East Liberty, were Saints Peter and Paul Church and School and the church in which I apprenticed in Catholicism; and Dilworth Schoolyard and Peabody Field where I apprenticed in baseball. So it was an overlap of places, collapsed within Pittsburgh like Babushka Dolls. But, as I’ve said earlier, place would not be as redolent in my work, and mean so much, had it not been for the orthodoxy of my Roman Catholicism – which I’ve touched upon already at some length – and the fact of my Italianata. When I was growing up, long before we lived in a hyphenated culture, we were Italians. We were not Italian-Americans. It was understood clearly that we were Americans. We needed no hyphen. We were Italian and of course we were Americans. Being Italian meant you lived in an Italian neighborhood. Your grandparents, for sure, and possibly your parents were born in Italy – and regardless of where they were born they spoke Italian. Everyone, absolutely everyone, ate pasta on the Sabbath and daylong the smell of sauce hovered deliciously over the neighborhood. The old men played bocci. The kids were allowed mouthfuls of wine. Everyone feasted on seven fishes on Christmas Eve. On Ash Wednesday, neighborhood foreheads were smudged with ashes. Everyone’s dead were interred at Mount Carmel Cemetery. At noon, when the Catholic church bells chimed The Angelus, people froze on a dime and prayed. I could go on. The behavior and culture were as codified as if etched in tablets of granite – as deeply as Pittsburgh and my life there, all those years ago, is etched in my psyche, in my very soul. It’s so rich and layered and tangible. I write so much about it that it seems like I still have a life there unabated, as if I’ve dispatched my doppelganger to walks those streets and mingle with all of those unforgettable people I’ve known and loved, living and dead. My love for it is unabashed and I can easily be goaded into sentimentality over it. I shall ever romanticize it. I’ve been blessed to have two homes, two tropes, two places – North and South – about which to write with what I hope is decided authenticity. Yet there are times when I’ve felt decidedly orphaned. For instance, one Thanksgiving Joan and I, and Jacob, only a few months old, set out from Anson County for Pittsburgh and the upcoming holiday. Just a few minutes into the journey, I stopped at a convenience store for coffee. The woman at the register remarked, “You’re not from around here. Are you?” I told her that in fact I was, that I had been living almost three years just down the road in Lilesville. “Hmm,” she said. Ten hours later, a few miles out of Pittsburgh, I stopped again for coffee. The fellow who took my money observed, “You’re not from around here. Are you?” I wasn’t sure how to respond, so I just smiled, thanked him and walked out the door. |

Return to Spring 2011 Table of Contents